This webpage contains resources from the Q methods study of vulnerability. These are intended to assist other researchers in systematically exploring controversial subjects such as vulnerability.

By sharing the project’s design, approach, and methods, the team hopes to encourage and support other researchers in adopting Q Methodology, particularly in the fields of social policy and policing where conflicting viewpoints exist.

Q Methodology is an effective technique to identify and explore areas of consensus and disagreement that integrates quantitative and qualitative analysis. In essence, Q Methodology involves participants ranking a set of statements on a given subject across a scale from “most agree” to “most disagree” (see fig 1). Q Methodology studies reveal shared viewpoints and highlight where opinions diverge. Further information about Q Methodology and its development are available below:

- Q Methodology

- Millar, Mason & Kidd (2022) “What is Q Methodology?” Evidence Based Nursing 25(3), 77-78.

Vulnerability is a widely used term but often does not have a clear or consistent definition. This creates challenges for public services in how they respond and support individuals who may be considered vulnerable.

In the UK, agencies including the police, healthcare providers, social care services, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have conflicting ideas about what makes someone vulnerable and how best to respond to their needs and allocate resources.

For example, a police officer may view some experiencing homelessness as ‘vulnerable’ due to their current situation and observable risks. However, healthcare professionals may link the same person’s ‘vulnerability’ to chronic conditions such as poor physical or mental health. Furthermore, a charity may take a broader view and consider all people experiencing homelessness ‘vulnerable’ and in need of support. The person experiencing homelessness may not see themselves as ‘vulnerable’ because of social networks or resources they can draw upon. People with these perspectives may all have different views about the role and value of vulnerability as an organising focus around which public services and police address situations of harm.

Q Methodology helps us understand these varied perspectives, identifying areas where agencies might have a shared understanding and areas where they disagree. Gaining this deeper insight is crucial for developing more effective and coordinated responses to addressing vulnerabilities in the context of policing and other allied public services.

The research question guiding this project is: “What are the impacts of how vulnerability is used in the work of policing and partner services in Bradford?”

To create the set of statements for participants to sort (known as the Q-set) the team began with a scoping review of 1,570 sources, including academic articles, policy documents and media reports, among others. This comprehensive review helped the team identify key themes and debates surrounding vulnerability across different sectors with a particular focus on policing. From this, the team developed 44 opinion statements, representing the ‘universe of opinions’ – the full scope of views on how vulnerability can be understood, responded to, and operationalised.

These 44 statements were presented to participants, who were asked to complete a ‘Q-sort.’ In the Q-sort, participants rank the statements by placing them on a grid, known as ‘the concourse’, that ranges from “most disagree” to “most agree”. In Q methodology, the statements are designed to probe viewpoints, so their tone is conversational and some are provocative.

To ensure the statements were clear, accessible and comprehensive, the team piloted them with two distinct groups. First, the team worked with a group of researchers specialising in vulnerability and policing to ensure that the statements over a wide range of opinions related to vulnerability. This was followed by a second pilot with two service providers and three individuals who accessed services at a mental health charity. This allowed the team to refine the statements’ language and clarity to ensure they could be easily understood by all participants, regardless of their background or experience.

The team’s final set of statements are shown below:

- ‘Bad girls’ aren’t seen as vulnerable

- Police officers are particularly vulnerable given the dangers they are exposed to

- People are often more fearful of social workers than police officers.

- Sharing personal information between public services can further harm vulnerable people

- Even some terrorists should be regarded as vulnerable

- Partnerships between police and social services will be dominated by the police

- It’s a good thing that policing is now more focused on vulnerability

- Many vulnerable victims never come to the attention of public services

- The police spend too much time investigating hate crimes

- Vulnerable people do not trust public services to protect them

- Vulnerability is another word for those who are socially disadvantaged

- A perpetrator’s vulnerability is not important when a serious crime has been committed

- The police treat everyone equally regardless of race and ethnicity

- Local charities do a better job at supporting vulnerable people than public services

- Calling someone vulnerable is offensive

- Diverting resources from the police to public health and other services would better support vulnerable people

- Public services are institutionally racist (not just the Police)

- The criminal justice system does a good job of serving vulnerable people

- The police have gone too soft in recent years

- Organisations fail vulnerable people because they lack funding

- Prioritising certain groups based on their vulnerability is the right thing to do

- For most vulnerable people, the police are the problem, not the solution

- The police fail to protect some vulnerable people because of institutional racism

- It is unfair when service providers decide who is vulnerable and who isn’t

- The police are in a good position to help vulnerable people

- Arresting vulnerable people can sometimes help them

- Even when people have experienced trauma, they need to take responsibility for their own actions

- The police are one of the few public services that can actually help people trapped in abusive relationships.

- Public services need to be able to share personal information about their service users more freely

- ‘Vulnerability’ is a term that helps different service providers to work better together

- Young offenders should be seen as children first, offenders second

- Vulnerable people often don’t see themselves as vulnerable

- The police should be left alone to do their job

- The police should focus on catching criminals, not helping vulnerable people

- Men hide their vulnerabilities

- The police should focus on improving young people’s difficult lives when dealing with gangs

- Vulnerable people who refuse to engage should never be forced to accept help

- Focusing on vulnerability draws attention away from issues of poverty and inequality

- The behaviour of victims is often a barrier to police investigations

- It’s routine practice for Police to abuse vulnerable people

- We should all be treated as vulnerable

- Vulnerability is a meaningless term

- The police should stop acting like social workers

- More attention should be given to preventing online abuse

An inverted bell-shaped concourse (Fig 1) is commonly used in Q Methodology as it encourages participants to distinguish the statements they feel most strongly about from a greater number that evoke more neutral feelings. By limiting the number of extreme placements, the concourse helps to reveal participants’ core beliefs and their most deeply held views on the topic.

Fig 1

To ensure participants had a common understanding of the sorting activity they were being asked to complete, the team prepared a video, which was shown to participants before completing the task:

After completing the Q-sort, each participant was interviewed for around 30 minutes (see questions below). This was to learn the reasoning behind their rankings, their opinions on certain key statements that the team felt spoke to the essence of the study (signal statements), and their understanding of the term ‘vulnerability’. The interview questions were tailored slightly differently for service provider (including police) participants and service user participants. This is so the team could determine how ‘vulnerability’ is used by providers in their everyday work and how its use was interpreted by service users.

Questions

The questions the team asked are listed below:

1. Why did you choose the four statements at the two extremes – ‘most agree’ and ‘most disagree’?

2. Signal statements:

- What do you think about?

- Many vulnerable victims never come to the attention of public services

- How do you feel about this statement?

- Calling someone vulnerable is offensive

- Why did you put that statement there?

- The police should focus on catching criminals, not helping vulnerable people

3. Any other particular statements that stood out for you? Can you explain why?

For service providers

4. Do you use the term vulnerability in the context of your work? If so, how?

Then probe:

- Is this useful?

- Any problems with this?

For service users

4. What would you think if professionals considered you as vulnerable?

5.

- What role do you think the police should play when it comes to vulnerable people?

- Is it beneficial/effective/important for the police to get more involved in responding to vulnerable people? Is it an appropriate role for the police? Any problem with this?

- Are police the best agency to respond to vulnerability?

The team also collected demographic data, including participants’ age, gender, ethnicity, employment status and disability status. For those accessing services, the team also acquired information on their interactions with the police, including whether they were suspects, had recent contact, or had frequent contact with the police. This data is known as the ‘P-Set’. In combination with the ‘Q-sort’ and qualitative data, the demographic data allowed the team to contextualise the findings.

Participants in Q study are those whose viewpoint about the subject (in our case, vulnerability) matters, rather than those who represent the population as a whole. For this study, the team identified three broad groups of people whose views were central to understanding views on the research question:

- frontline police

- other public and voluntary sector service providers who work with and support vulnerable people in contact with policing, and

- ‘services users’ i.e. members of the public who access local services or have contact with police, many of whom may be described as ‘vulnerable’.

Service provision for vulnerable people varies considerably across local areas. So, the team decided to focus its P-Set on people living or working in the city of Bradford, which has also been the focus of other projects within the Centre’s programme of place-based research. Consequently, the team purposefully selected 61 individuals based in the city of Bradford, including:

- 18 frontline police officers

- 18 service providers from sectors such as housing, health, education, and drug services

- 25 members of the public with direct experience of accessing a diverse range of local services, including homelessness support, drugs and alcohol support, youth services, community centres, and food banks. Many of these service users had also had direct interactions with the police. The participant ages ranged from 16 to 62 years old.

All participants (n=61)

- Average age: 37.7 years

- Women %: 57% (35)

- Racially minoritised %: 33% (20)

- Working full time %: 61% (37)

- Disability %: 10 % (6)

Service users (n=25)

- Any police interaction: 80% (20)

- Police interaction as a suspect: 36% (9)

- Police contact in the last 12 months: 24% (6)

- Police contact more than once a year: 24% (6)

In Q methodology, a ‘factor’ represents a shared pattern of thinking or a common viewpoint among participants, identified through the statistical analysis of their Q-sorts, which groups individuals based on how similarly they have ranked the statements in the study. Our study used KenQ Analysis Desktop Edition (KADE), a free software that helps apply Q methodology, to analyse intercorrelation between Q sorts, known as the factor analysis.

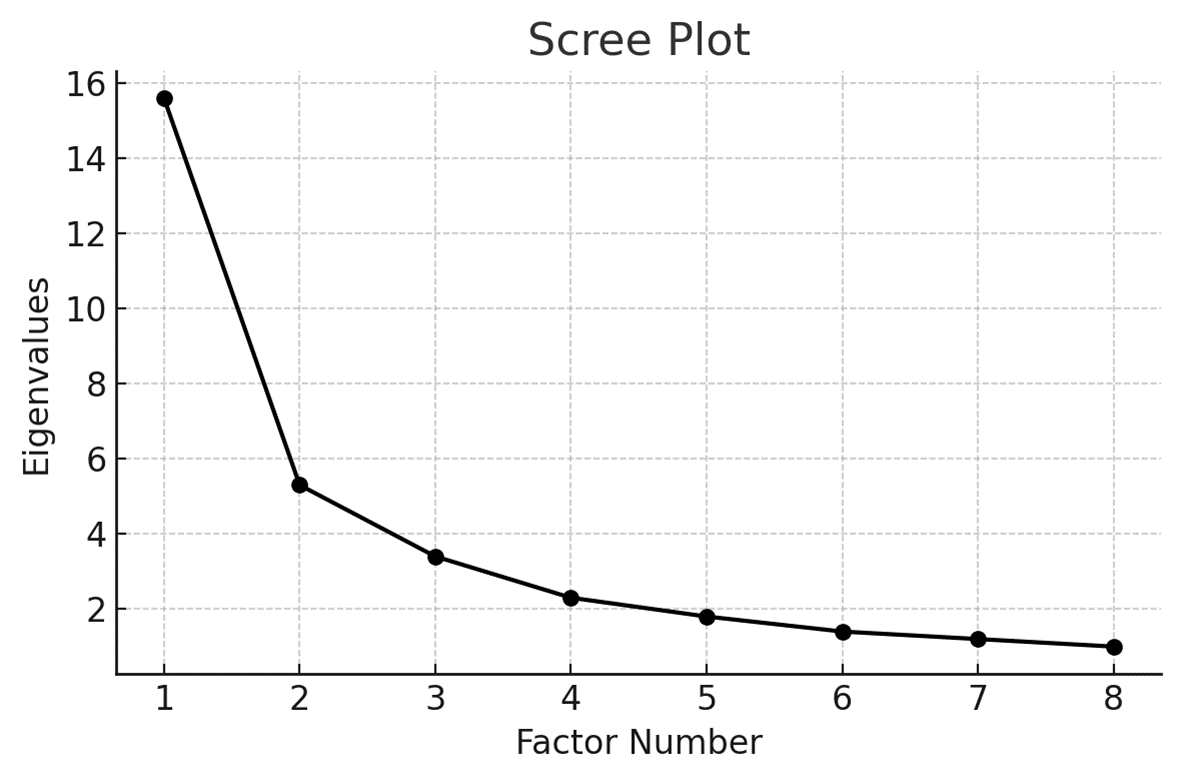

The team then applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA) – the most common factor extraction method and commonly used in Q-methodology – to identify participants who sorted their Q sort similarly. At the end of this process, the researchers extracted eight principal components, i.e. patterns which summarised the most important commonalities in participants’ rankings. The analysis showed that the number of pattern options (or factors) ranged from 8 to 1 (i.e. from 8 smaller groupings to one large group with all participants in). The research team needed to then make a decision about the number of factors to opt for. In consultation with a Q methods expert, three factors were chosen based on several criteria (see Figure 2):

- The eigenvalue threshold: Eigenvalues show how much variation each factor explains. The team only retained factors with an eigenvalue of >1. (see figure 2)

- The ‘magical number 7’: The team followed a common guideline used in Q Methodology software, which suggests working with seven factors).

- Significant Factor Loadings (SFL): The team worked with the requirement that each factor must have at least two participants that strongly matched it.

- Additionally, the ‘Humphrey rule’ was applied, which states that a factor is significant if the cross-product of its two highest loadings exceeds twice the standard error (this rule helps to ensure that the factor is stable and not based on random variation).

Figure 2: Eigenvalues and line plot.

Factor 1 explained 64.2% of the variation in how people ranked their views on policing vulnerability. Factor 2 explained 21.8% and Factor 3 explained 14% of the variation. In Figure 2, you can see the point where the slope changes, known as the line plot, which shows where the importance of each factor starts to drop. The relative difference in eigenvalue across the initial eight factors diminished considerably, beyond the first three. So, in light of these checks and balances (see figure 3), the team decided to retain the first three factors because they explained the most significant variation.

Figure 3: Lists of the multiple criteria for selecting the factors

| 2 factors | 3 factors | 4 factors | 5 factors | 6 factors | 7 factors | 8 factors | |

| SFL | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Humphrey | Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | No | No | No | No |

| Line plot | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Interview data | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

After identifying the three main factors, the team looked closely at how participants fitted into them. Four Q-sorts (3 service users, 1 police) lacked strong association to the factors selected, so were excluded to keep the results as accurate as possible. One Q-sort mapped onto Factor 2 but in a ‘bipolar way’ meaning that the view expressed was the diametrical opposite of Factor 2.

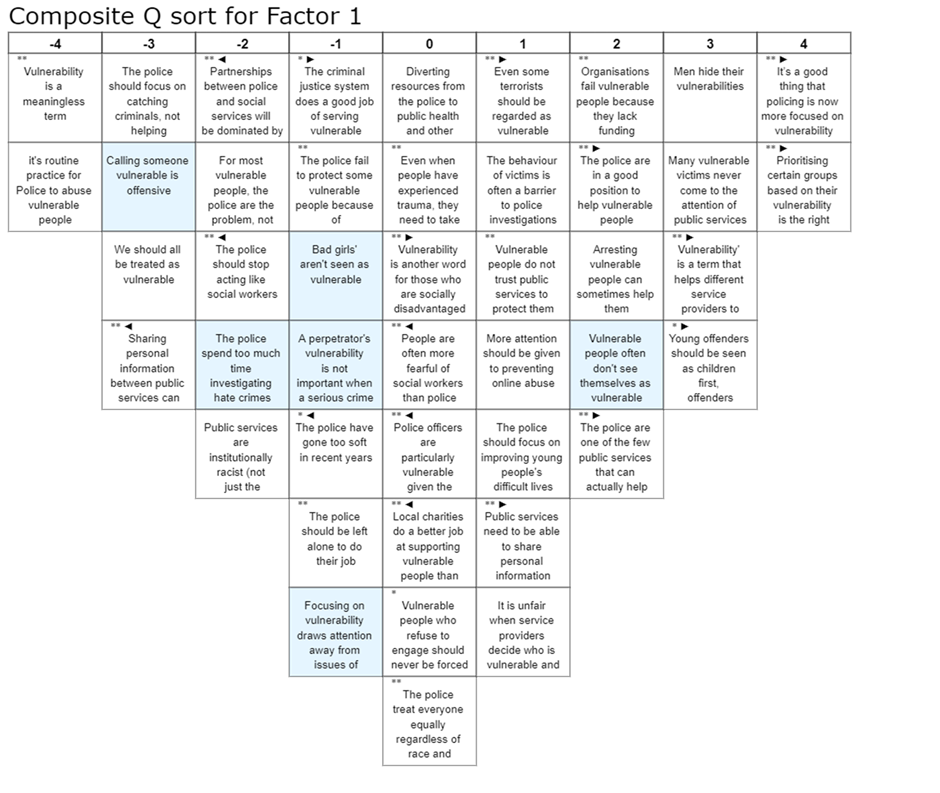

The software illustrated the shared viewpoints in the form of idealised Q-sorts (see Fig 4), detailing which participant’s sorts were clustered together, and correlated with these idealised views. This allowed the team to identify different viewpoints on the topic. Moreover, the analysis also showed areas of consensus across different viewpoints by identifying the statements that all participants ranked similarly (known as ‘consensus statements’, which are highlighted in blue in the table below).

Figure 4: Composite Q-sort for Factor 1

In addition to the Q-sort analysis, the qualitative and demographic data collected through follow-up interviews was crucial for creating a narrative that describes the shared viewpoints. All qualitative responses to the ‘signal statements’ and the two most commonly selected ‘most agree’ and ‘most disagree’ statements in each factor were coded in NVivo to provide qualitative insights into the most strongly held opinions.

The study revealed three distinct viewpoints on how vulnerability is addressed by police and public services in Bradford.

- Viewpoint 1 strongly endorses a vulnerability focus for police and public services to deliver improved outcomes in situations of harm.

- Viewpoint 2 is sceptical of police and public services’ ability to address vulnerabilities, underscoring distrust of authorities and institutional failings.

- Viewpoint 3 is also sceptical of the police and public services’ capacity to support vulnerable people, emphasising inadequate resourcing, the vulnerability of police officers and the need to prioritise crime-fighting duties.

For a detailed account of our findings, you can read the research summary report.

These findings have implications within the UK and internationally around the challenges and opportunities a greater focus on vulnerability in policing and public service delivery presents. Replicating this study (or similar) in other areas with different cultural contexts or policing models could help uncover how diverse approaches to vulnerability influence outcomes for those most at risk.

We welcome use of any of our tools or approaches to further explore the complex issues of vulnerability and policing. If you’re interested in replicating or building on this work, collaborating or learning more, feel free to reach out to the team at: vulnerabilitypolicing@york.ac.uk.