18 November 2024

Research team: Professor Ben Bradford, UCL; Dr David Rowlands, University of Leeds; Dr Christine A. Weirich, University of Leeds; and Professor Adam Crawford, Universities of York and Leeds.

- The public does not think police are meeting what they see as minimum standards of service delivery.

- Many people do not think the police are currently a visible, viable and engaged presence in their communities.

- Negative judgements about police performance are feeding into wider concerns. Many lack confidence in police and question the legitimacy of police. Nonetheless, the public retain significant trust in the idea, and the figure, of ‘the police’.

- Current efforts to reverse declining confidence in policing stress internal reform, greater efforts to fight crime, and revitalising neighbourhood policing. Though all are important, this research suggests that the last of these is likely to be most vital.

Summary

The relationship between police and public is currently an issue of significant concern. According to some metrics, trust and confidence are at their lowest ebb for 20 years. Aiming to go beyond established indicators such as perceptions of ‘how good a job’ local police are doing; we created a nationally representative survey based on the Minimum Policing Standard.

Alongside a range of other measures, 18 survey items probed views on the extent to which police are achieving minimum standards across three domains:

- Response to calls for service and other contact

- Behaviour and Treatment in relation to the public

- Presence and Engagement in local communities.

Overall, people think police are falling far short of providing the service they should. Our findings concur with the idea that there is currently a crisis of confidence in police and police legitimacy. Yet, viewed from another perspective public trust in police remains stubbornly and perhaps surprisingly high.

Background

Relations between police and public are currently at a low ebb. The service has been beset by multiple scandals and other problems, many of which are thought to impact on public opinion.

On many measures, trust and confidence in the police have been falling for nearly a decade, reaching levels not seen since the early 2000s. This has sparked renewed policy and academic interest in questions of public trust and police legitimacy, much of which relies on survey evidence to understand the trends in and sources of people’s views of the police.

Many current surveys of attitudes towards police have several features in common. They reuse questions from other surveys, some of which are now 40 years old. They frequently rely on single item measures of key constructs (e.g., “how much do you trust police”). And most survey items, whether well-established or new, are fielded because they are of interest to the surveyors, not necessarily the people being surveyed.

There are good reasons for all these choices, including maintaining the consistent time series that allow us to identify declining trust and confidence. However, they risk missing what is most important to the people being surveyed, the people who, after all, police are meant to serve.

We wanted to try a different approach. We used the criteria developed in our earlier work on the Minimum Policing Standard to come up with a set of survey questions grounded in what the public thinks is important in and for the policing they experience in their communities. Knowing what people think about local policing, in terms that are relevant to them, should provide important information for efforts to enhance trust and confidence.

What we did

We commissioned polling company Verian to conduct a population representative survey of England, Wales and Scotland that fielded questions developed from our work on developing the Minimum Policing Standard.

These covered the three domains of Response, Behaviour and Treatment, and Presence and Engagement (see Figures 1 to 3). Alongside the Minimum Policing Standard items we fielded a range of other questions, covering public attitudes towards police and contact with officers, views on the limits and boundaries of policing, and when behaviours or issues warrant or require police intervention.

We distinguished between different, and often conflated, aspects of people’s views of and attitudes toward police, e.g. legitimacy and trust. Legitimacy is a subjective assessment of the police’s ‘right to rule’, and of the reciprocal duties this places on the policed. Trust is a willingness to be vulnerable to police that is based on positive evaluations and expectations of competence, benevolence and good intentions. The Minimum Policing Standard items can be thought of as measures of confidence in police, a conscious evaluation of whether police are trustworthy – i.e. whether they are in fact competent, benevolent and well-intentioned.

Key findings

Many people do not think police are meeting minimum standards of service provision. Figure 1 covers the Response domain, showing the proportion of people agreeing with each statement. There are two bars for each indicator: the darker line gives the percentage calculated with ‘don’t know’ responses excluded, while the lighter line gives the percentage calculated while retaining ‘don’t knows’.

The Minimum Policing Standard items garnered high numbers of such responses – up to a third in a few cases – indicating a lack of certainty, knowledge or simple awareness among some respondents. Survey results are usually shown with ‘don’t know’ responses excluded. But given the way the Minimum Policing Standard items were derived, they should arguably be retained here. A ‘don’t know’ response indicates at the very least uncertainty or a lack of confidence about whether a particular standard is being met.

Whether or not ‘don’t knows’ are retained, no Response indicator achieves more than 50% positive responses; most have less than 40%, and less than 30% are confident that police are open and transparent with the decisions they make, prioritise the crimes most affecting their community, and provide adequate follow up after a crime has been committed.

Figure 1: Response domain

Percentage agreeing with each statement that the police…

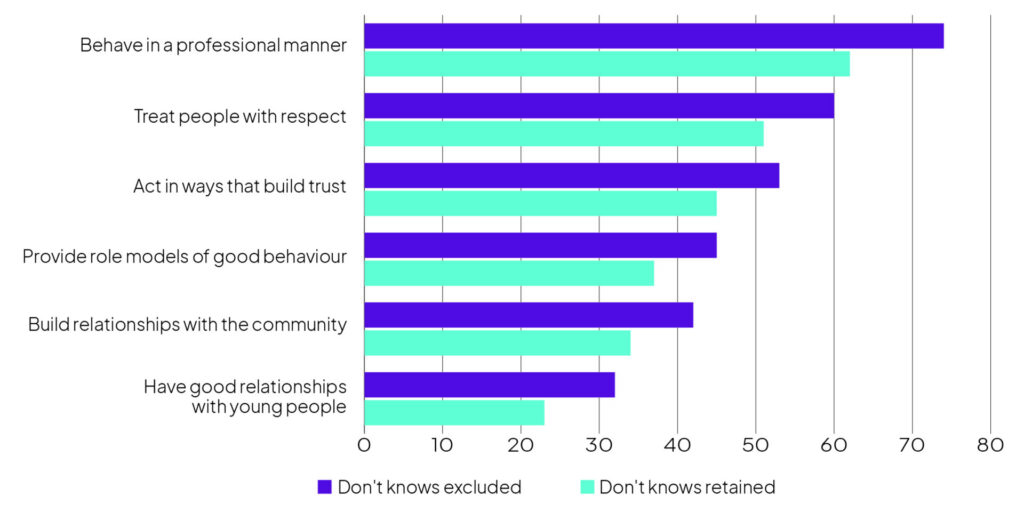

Figure 2 repeats the process for the Behaviour and Treatment domain. Here, responses are more positive – people have relatively high levels of confidence that police behave in a professional manner and treat people with respect, for example.

That said, significantly less than half believe police provide good role models of behaviour, build relationships with the community, and have good relationships with young people.

Figure 2: Behaviour and Treatment domain

Percentage agreeing with each statement that the police…

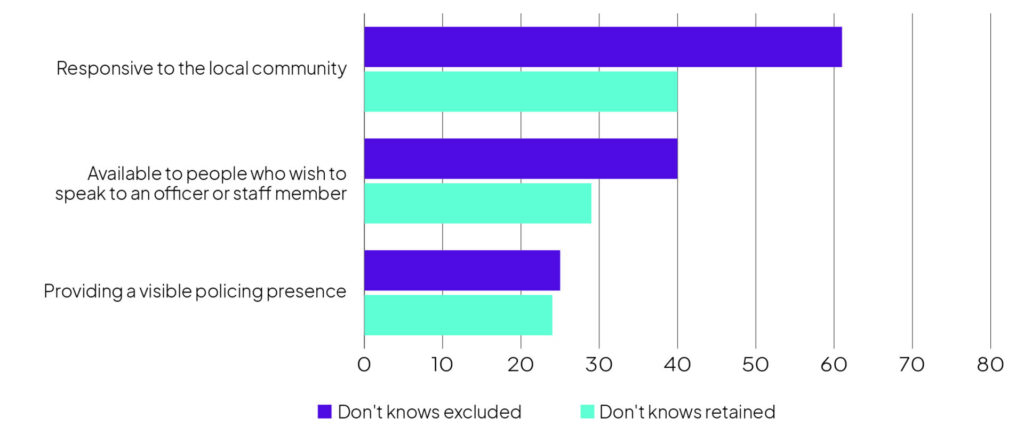

Results from the Presence and Engagement domain are shown in Figure 3. Here, the picture is more akin to the Response domain, particularly regarding police being available to people who wish to speak to them and providing a visible police presence. Overall, people do not seem to think police are present enough in their communities.

The findings from our survey resonate strongly with the idea of a crisis in police-public relations. Some of the lower scores outlined above indicate worryingly low levels of confidence that police are meeting basic levels of service provision; although there are significant variation across the different indicators, and some are much more positive.

Figure 3: Presence and Engagement domain

Percentage who say that all or most of the time the police are…

Public confidence in policing therefore seems currently weak, at best. But other indicators included in the survey suggest that people retain significantly higher levels of trust in police, particularly if they are asked to think about individual officers. Some 65% agree with the statement “I am happy to accept the ability of the police to intervene in people’s lives”, while 90% say they would feel very or fairly safe if they found themselves alone with a uniformed police officer (compared with 84% for social workers and 97% for medical professionals).

We also explored the correlation between the Minimum Policing Standard domains and other commonly used measures of public opinion. Aligning with the idea of procedural justice, we found that the Response domain, which covers the way police treat and build relationships with people and communities, was the strongest predictor of police legitimacy and trust in the police. Both trust and legitimacy are premised most importantly in judgements about how officers treat people and concerns about the relationship between police and public.

However, we also found that all three domains were associated with overall confidence – as measured by judgements about ‘how good a job’ local police are doing – with Presence and Engagement the most important factor. When it comes to public confidence in police, it seems that people attend to all the different aspects of police activity, and in particular questions of presence and availability.

Next steps

Current efforts to improve the relationship between police and public revolve primarily around three core issues:

- Demonstrating effectiveness in ‘the fight against crime’;

- Internal reform to weed out unsuitable officers, hire more suitable ones, and provide training that improves interactions with the public; and

- Revitalising neighbourhood policing.

Our work on the Minimum Policing Standard indicate all three are important, but also that neighbourhood policing is the most important. When asked, the public seem to prioritise this element of policing, and police reform, the most.

People also tend to take a very process-based view of policing – when it comes to questions of trust, legitimacy and confidence they are less concerned with ‘success’ in reducing crime than is often assumed, and more concerned with how policing is conducted, perhaps particularly in terms of relationship building. And while internal reform is vital for a whole host of reasons, people already have quite positive views of the trustworthiness of individual police officers, making it difficult to achieve large improvements in this domain.

Where people feel policing is really lacking, though, is in visibility and availability in their neighbourhoods, and in building relationships with individuals and communities. This is why neighbourhood policing is so important. Yet, some of the areas in which people feel policing is falling shortest – fast responses to calls for service, making an effort to investigate all crimes, prioritising locally important issues, policing that is visible in all communities – may be difficult to achieve given current pressures on and priorities in policing. The contemporary focus on high-harm, often hidden offences, on the one hand, and the need for police to step into gaps left in the fabric of social security as other services withdraw due to budget cuts and other pressures, on the other, suggest that police priorities and public desires are out of kilter. Are police willing, let alone able, to meet the standards people set for them, and what would it mean for policing if they tried?

There are no easy answers to this conundrum. Certainly, it would be entirely inappropriate for police to shift attention away from high harm crimes because this would free up resource to give the wider public ‘more of what it wants’. But the nuanced insight into public views of policing provided by the Minimum Policing Standard should provide the basis for more contextualised and hopefully effective efforts to improve police-public relations that are both realistic in terms of the likelihood of success and recognise the challenges posed by resource constraints and the multiple pressures on police.

Our research suggests that if police achieve a minimum standard in the delivery of local policing, this will build trust and confidence, and members of the public will be more likely to trust them to do other activities well, and to accept that some of the other, less visible aspects of police work, are being conducted appropriately. We hope to focus more closely on this idea in future work.

Contacts

- Lead Investigator: Professor Ben Bradford, [email protected]

- Centre Co-Director: Professor Adam Crawford, [email protected]

The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged. Grant reference number: ES/W002248/1.

Appendix

The data reported here are drawn from a survey of the Public Voice panel managed by Verian (formerly Kantar Public), who were commissioned in the autumn of 2023 to run a survey with a target respondent sample of 1,500. The target population was individuals aged 18+ and living in residential accommodation in Britain. The sample comprised 1,000 respondents across Britain, plus a ‘boost’ of 500 respondents living in the most deprived fifth of each country (England, Scotland and Wales).

At the time the survey was conducted (November 2023), the Public Voice panel comprised 22,142 members in England, Scotland and Wales. Most were recruited via the Address Based Online Surveying method, in which (probabilistically) sampled individuals complete a 20-minute recruitment questionnaire either online or on paper.

Recruitment surveys were carried out in 2019, 2020 and 2021 and the respondent samples have been linked together via a weighting protocol to form a single panel. The sample for the current survey was drawn from this panel. The panel was stratified by the Neighbourhood Index of Multiple Deprivation, and then by sex/age, before a systematic random sample was drawn. In total, 4,888 panel members were issued to the field, and the survey closed on 20 December 2023 with 1,517 completions, of whom 1,484 based quality control tests and constitute the basic sample used here. The overall conversion rate was 30%. All surveys were completed online, and those who completed the survey were offered a £10 voucher.